Paramadina Public Policy Review, 19 January 2018

Indonesia’s Tabungan Haji seems to accommodate the demand of the Indonesian Muslims for Hajj effectively. The number of new account openings keeps increasing, regardless of the long wait times. To this end, the institutional economics perspective has helped explain how the government-regulated-and-promoted Hajj saving arrangement successfully mitigates future risks of failing to perform the Hajj. The scheme seems to take advantage of the Muslims’ cognitive dissonance over potential risks and uncertainties.

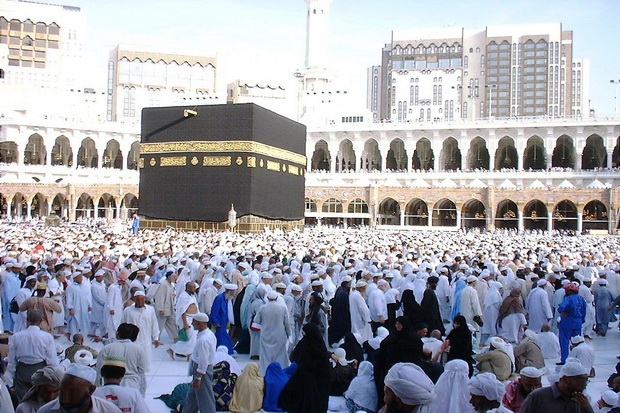

For Muslims, performing the Hajj in Mecca is a crucial devotion to one of the Five Pillars of Islam and is highly encouraged to be done at least once in a lifetime. Especially for Indonesian Muslims, the Hajj marks their highest religious achievement, and to some extent, it will lift their social status. But for the Indonesian government, the Hajj is a policy challenge.

REGULATED AND PROMOTED BY THE GOVERNMENT

The Hajj Law, Law no 13/2008, governs the Hajj management in Indonesia, which regulates many aspects from Hajj quota distribution to bank appointments for administering Hajj savings (Kemenag RI, 2012). Regarding the arrangements, the Religious Affairs Minister determines which banks are eligible to assist Tabungan Haji, the Indonesian Hajj saving scheme this essay focuses on.

The savings scheme requires that Indonesian Muslims who want to perform the Hajj initially deposit IDR 25 million or around US$1925 in any of the appointed banks. Once the initial deposit is fulfilled, the ‘Hajj candidates’ can register themselves with the ministry and deposit the fund into a national Hajj fund fully under government control (Kemenag RI, 2012). The candidates then receive portion numbers which tell them when to depart for the Hajj (Kemenag RI, 2012).

Due to the relatively limited quota given by the Saudi government, the wait times are quite long, ranging from 12 to 17 years across different provinces. When their turn comes, the candidate should have made the total payment, around Rp35 million or US$ 2850. (Detikcom, 2017), meaning some additional money to the initial deposit is required.

Regardless of the long wait times, Tabungan Haji still attracts about 500,000 people annually to open Hajj saving accounts and start saving (Sudiarto, n.d.). Because the average annual income of Indonesians is around US$ 1650, to reach the initial deposit will take quite some time to save, since generally, people only keep around US$ 10–50 monthly for savings.

ANALYSIS OF THE SAVINGS SCHEME: AN INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE

There are at least two important aspects of the savings scheme to be considered. First, the government decided not to build a single financial organization to administer the savings plan, unlike its neighbor Malaysia, which has such an organization called Tabung Haji (Ishak, 2011). Secondly, the appointed banks are given the right to administer the scheme and add variations to the service, such as the different minimum initial deposits among the banks (Infoperbankan, 2017).

Regarding the amount of the fund, the ministry collects at least around Rp12.5 trillion or US$840 million every year. It contributes to the total fund managed by the ministry, amounting to approximately Rp70 trillion (2017), which so far is mostly placed in sharia securities (Sudiarto, n.d.).

To this end, as stipulated by the Hajj Law, the bank appointment seems to be the way the Indonesian government has chosen to mitigate uncertainties and reduce transaction costs. The government uses its power to order appointed banks to help reach Muslims across the archipelago and encourage them to start opening Hajj savings. From the perspective of institutional economics, this arguably resonates with Williamson’s (2000) third level of social analysis.

Williamson (2000) sees that through four levels of social analysis, institutional economics can help analyze societal processes on formal and informal rules that shape the public’s social, economic, and political behavior, especially toward transaction costs and risk mitigation. At the third level, Williamson explains the role of ‘the play of the game’, which means the governance of contractual relationships among, as Caballero and Soto-Oñate (2016) interpret, players from different organizations. In a real-world application, the governance in practice reduces economic transaction costs, obtains efficient economic performance (Caballero & Soto-Oñate, 2016), mitigates potential conflicts, and gains mutual benefits (Williamson, 2000).

As the government has set the rules based on the Law, the bank appointment alongside the service variation provided reflects the application of the game’s play or the contractual relations between the government and the banks. Furthermore, the system reduces transaction costs by creating an atmosphere that getting to the first step to perform the Hajj is very affordable, especially for general Indonesian Muslims. The government helps them focus on preparing an efficient Hajj management without worrying that the Hajj candidates’ failed payment when their turns show up.

FURTHER ANALYSIS: ACCOMMODATING MUSLIMS’ BIAS

Though, the given limited quota, the high demand for Hajj, and the long wait times have caused risks and uncertainties to some extent. First, reaching the minimum deposit to be registered takes years for Indonesian Muslims in general. Secondly, in 12-17 years, those registered but still on the waiting list may have lost their opportunity to perform the Hajj because of many reasons, including dying before their turn comes. Thirdly, managing the total deposited Hajj fund requires a great deal of management, let alone the management of the un-deposited funds.

Those risks indicate that there is a probability that even once registered, a candidate may or may not perform the Hajj. Every year, news about Hajj candidates passing away is always the media. Concerning the third risk, a recent corruption case has resulted in a jail sentence for the previous Religious Affairs Minister due to gratification allegation on mismanagement of the Hajj fund. Logically, these risks should be enough to discourage Indonesian Muslims from dealing with Hajj savings and to find other ways to perform the Hajj. But in reality, the rate of opening Hajj savings accounts continues to increase annually (Kontan, 2010).

To explain this illogical circumstance, it is interesting to see how cognitive dissonance creates a bias for economic decision-making. It reflects the notion when potential negative outcomes are well-understood, but a coercion-free commitment is still undertaken to maximize utilization (Gilad, Kaish, & Loeb, 1987).

In the Indonesian Hajj savings context, selective exposure allows the Hajj candidates to ignore the aforementioned risks. Instead, they focus on their religious desire to be devout Muslims by performing the Hajj. For example, in my community, I see how people in their mid-50s with an annual income less than US$1000 still opt for the Hajj savings. Regarding the risks of uncertain fulfillment of the minimum deposit requirement, this decision does not make sense economically.

However, it seems that the provision of Tabungan Haji itself prompts these people to continue participating in the savings scheme. Of the general Hajj saving policy, the arrangement could explain the possible reasons for this biased circumstance.

Firstly, the minimum deposit, which is lower than the real cost, is reckoned to effectively accommodate Indonesian Muslims’ perceived possibility of performing Hajj, regardless of uncertainties such as the long waits and the higher real costs. In other words, it keeps alive their hopes of performing the Hajj during their lifetime, no matter what. Secondly, the bank appointments are attractive to banks, enabling them to increase funds collection for business reasons, and at the same time, helping to accommodate the strong religious desire of Muslims to be Hajj candidates by opening Hajj savings. The various services given by the appointed banks are attractive to Muslims as they provide different options for Muslims’ various preferences and economic levels.

CONCLUSION

Because the number of new account openings keeps increasing, Indonesia’s Tabungan Haji seems to accommodate the demand of the Indonesian Muslims for Hajj effectively. In addition, the length of the wait times does not stop people from starting to save for Hajj. To this end, the institutional economics perspective has helped explain how the government-regulated-and-promoted Hajj saving arrangement successfully mitigates future risks of failing to perform the Hajj.

The contractual relationship between the government and the appointed banks allows the Hajj management in Indonesia to continue being well-managed and accommodate the demand well. Moreover, the scheme seems to take advantage of the Muslims’ cognitive dissonance over potential risks and uncertainties, such as the uncertain time of the initial deposit completion, long wait times once the candidate has registered, and possible fund corruption. (*)

REFERENCES

Caballero, G., & Soto-Oñate, D. (2016). Why transaction costs are so relevant in political governance ? A new institutional survey. Revista de Economia Politica, 36(2), 330–352. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-31572016v36n02a05

Detikcom. (2017). Jokowi Sudah Teken Keppres Biaya Haji Tahun 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2017, from https://news.detik.com/berita/d-3465009/jokowi-sudah-teken-keppres-biaya-haji-tahun-2017

Gilad, B., Kaish, S., & Loeb, P. D. (1987). Cognitive dissonance and utility maximization. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 8(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(87)90021-7

Infoperbankan. (2017). 5 Tabungan Haji yang Bagus untuk Anda. Retrieved June 21, 2017, from https://www.infoperbankan.com/umum/5-tabungan-haji-yang-bagus-untuk-anda.html

Ishak, M. S. H. (2011). Tabung Haji as an Islamic Financial Institution for Sustainable Economic Development. 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences, 17, 236–240.

Kemenag RI. (2012). Kebijakan Penyelenggaraan Ibadah Haji. Retrieved June 21, 2017, from http://haji.kemenag.go.id/v3/content/modul-iii-kebijakan-penyelenggaraan-ibadah-haji

Kontan. (2010). Rutin mencicil, agar bisa naik haji. Retrieved June 21, 2017, from http://keuangan.kontan.co.id/news/rutin-mencicil-agar-bisa-naik-haji-1

Solopos. (2017). 20 Calon Haji Solo Meninggal Dunia Sebelum Berangkat. Retrieved June 21, 2017, from http://www.solopos.com/2017/03/19/20-calon-haji-solo-meninggal-dunia-sebelum-berangkat-802829

Sudiarto, A. (n.d.). Developing Islamic Financial Centers In Indonesia and Opportunity & Challenges of Islamic Banking. Retrieved June 21, 2017, from https://business.smu.edu.sg/sites/business.smu.edu.sg/files/AFLP/ModuleAgenda/ppt/Mod3A/9 Slides_Day03_Session05_Agus.pdf

Williamson, O. E. (2000). The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595