The Economist, 2015

Millions of spectators from all over the world—including thousands of Indonesians, who stayed up until the early hours—tuned in to watch the Spanish football league’s premier fixture in October 2014.

The match, also known as El Clasico, is the faceoff between La Liga’s two greatest teams: Real Madrid and Barcelona. Like the British Premier League, or the German Bundesliga, La Liga is a multi-billion dollar enterprise—with millions of viewers drawn in the quality of the football. And one reason why La Liga generates such skilled playing is because its referees stringently enforce the rules of the game. The world of investment is not so different and just like La Liga, Indonesia needs clear and fair rules to attract global investment and to allow its economy to flourish.

Unlocking Indonesia’s potential

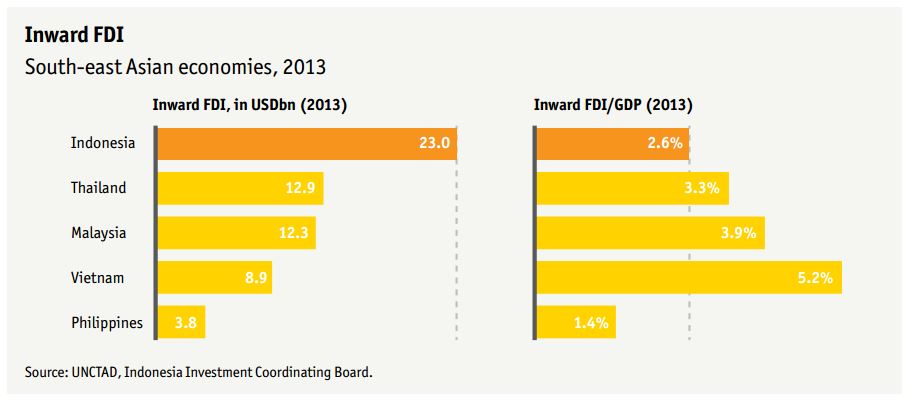

Home to about 40% of South-east Asia’s population, land mass and economic capacity, Indonesia is a country with huge economic potential. But there is a disparity between potential and reality. For example, despite huge foreign direct investment growth over the past decade, Indonesia’s FDI to GDP ratio is still only 2.6%, half that of Vietnam. Investment faces three main obstacles: policy uncertainty, infrastructure reliability and quality of human capital.

Improving human capital and infrastructure will take time and will require mid-to long-term solutions, but improving policy could have an immediate impact and should be a top priority for the current administration. Businesses can fluctuating currency and high inflation by hedging currencies and sharing the impact of rising costs with consumers.

However, companies are powerless in the face of policy uncertainty. Fortunately improving policy is not expensive—which is convenient as the government faces a challenging fiscal situation—and will lead to solutions in all other areas, including infrastructure and human capital.

Lack of policy applicability

Many issues can create policy uncertainty. One of the most troublesome in Indonesia is the lack of policy applicability, which can create unnecessary costs and limit the opportunity for the private sector to tap business opportunities. For example, Government Regulation No.82 of 2012 on Implementation of Electronic Systems and Transactions (GR 82) mandates Indonesian businesses conducting electronic transactions provide a public service and must set up localised data centres in Indonesia. Yet, the law has created confusion as it does not define what public service means.

GR 82 requires every electronic system provider operating in Indonesia to be registered and have a data centre in the country. This requirement aims to help the government locate and control data within Indonesia’s sovereign territory and protect against cyber-crime. But, it is expensive and inconvenient for information and communications technology companies to meet this requirement. And, it also has an impact on the banking and insurance sectors.

One major issue with GR 82 is the availability of a reliable power supply, with the sole provider being state-owned electricity company Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN). Even in Java, where the capital is located, power outages are common and many e-commerce businesses will be reluctant to rely on PLN as their sole source of electricity. This is bad news for small- and medium-sized technology firms that will be unable to afford their own data-centre, let alone a distributed power solution to protect it against outages. Renting space from a domestic data-provider would also create additional costs. Furthermore, cloud computing is being increasingly adopted around the world because of the efficiency it offers, and GR 82 will put Indonesian companies at a disadvantage.

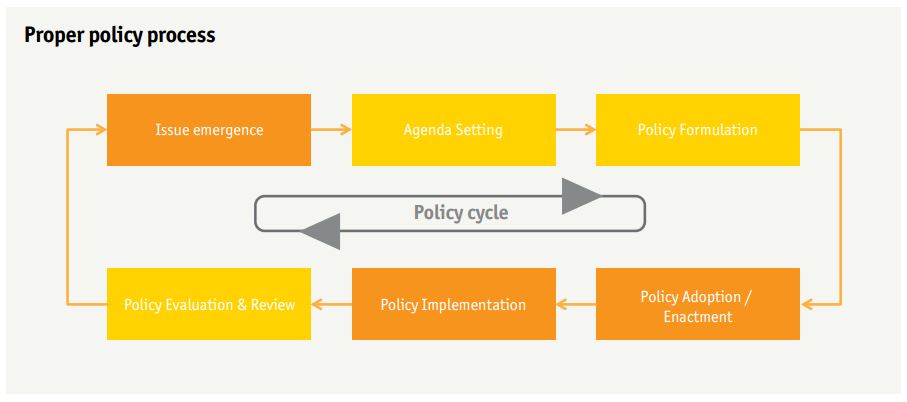

To avoid the enactment of poorly thought-out legislation there needs to be more consultation between business and government. Ideally, the government should engage the business community in the policy-making process, and the business community should proactively seek dialogue with government. Ultimately, businesses are a part of implementing these policies, and their input and insights are valuable. In fact, according to Indonesian law, the business community and broader society are entitled to oral or written input in the discussion and formulation of draft laws and regulations.

Business must take a more active role in the policy cycle by:

• Setting the policy agenda—through public discourse or regular dialogue with policy makers—to ensure that the concerns of the business community become government priorities;

• Participating in the formulation of policy by collaborating with think-tanks or universities to prepare evidence-based recommendations for the government;

• Reviewing policy to give input to the government on potential improvements based on industry changes.

Foreign ownership

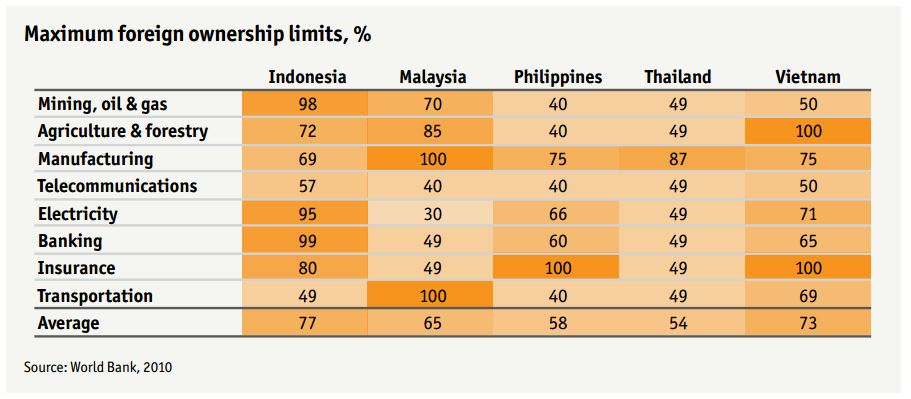

Policy on foreign ownership has been a recurrent issue in the Reformasi period, and public sentiment towards foreign companies swings back and forth from negative to positive.

Politicians often drum up support prior to legislative and presidential elections by pandering to nationalist sentiment. Periodically, the House of Representatives (DPR) has come close to placing restrictions on foreign ownership of companies in various sectors in recent years. But despite these periodic threats, Indonesia is more open relative to its peers in the region. Ideally, limits on foreign ownership will need to be at a level that makes investing in Indonesia still attractive to foreign companies. Policy adjustment must be managed and executed properly, under fair business practices and in a realistic timeframe, to avoid deterring investment.

Regulation

Lack of harmony in the regulatory landscape has become a serious issue since the decentralisation “big-bang” in 2001. Within one year more than 500 sub-national governments became autonomous with the authority to collect revenues, formulate budgets, implement development plans and issue regulations. But problems have arisen as national and sub-national regulations have come into conflict, with the latter often-lacking coherence.

Paramadina Public Policy Institute’s new study, “Indonesia’s New Path: Promoting Investment, Nurturing Prosperity”, illustrates how companies operating across Indonesia have to comply with different local regulation in hundreds of districts. The complexities and costs are enormous.

Another obstacle to investment opportunities is national infrastructure development. Each district has its own local government regulation regarding land use planning (RUTR) that may not be in line with national development plans. In instances when the central government has tried to implement an infrastructure project, such as a power plant, port or toll road, the plans have often conflicted with the local RUTR. Unfortunately, RUTR adjustment requires the approval of the given sub-national legislature. This involves a political process that is often lengthy, complicated and expensive. MP3EI, former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s programme to speed up infrastructure development, has experienced serious delays with many attributable to RUTR issues.

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MoHA) has the authority to review sub-national government regulations. However, MoHA has a limited capacity and mountains of regulations to review. It is estimated that each year around 5,000 sub-national regulations are issued. Adding to the problem is a rule by which local regulations become effective if there is no comment from the MoHA within 60 days. This means that many local regulations become law without proper review and consequently may not align with each other, creating unnecessary complexity, costs and business uncertainty. Empowering MoHA should become a top priority of the government.

The next five years

The administration of President Joko Widodo must address a faltering economy due to declining global commodity prices. Commodities and commodity-related products represent around 40% of Indonesia’s exports and play an important role in the domestic economy; as a result economic growth has slowed from 6.4% in 2011 to around 5% in 2014. The government’s budget is targeting growth of 5.8% in 2015 and 7% or higher by 2019. Meeting these targets will be a challenge, and the Paramadina Public Policy Institute estimates that it will require investment of around US$290bn. Without massive private sector contribution this will not be achieved.

Fortunately, the administration is aware of this situation and is showing its commitment to improve the business environment in Indonesia by reducing red tape, improving infrastructure and simplifying the business approval process. It is very likely that during the first year of their term they will make various strategic policy reforms to take advantage of Jokowi’s strong political capital. The recent fuel price increase has proven his willingness to implement unpopular but important policies for the country.

Good times create bad policy and bad times create good policy—and now Indonesia has the perfect combination. I anticipate a long list of policy reforms over the next five years, particularly in priority areas like energy and food security, taxation and investment.

Right now Indonesia must make some tough decisions and the next five years is a period of make or break. Policy reform will be key to ensuring standardised sets of rules make business in Indonesia fair and profitable. The Middle East economies of the United Arab Emirates and Qatar are far more economically vibrant than other countries in the region because they have observed this lesson. The initial signs are that the current administration understands this too, and will seek to level the playing field to attract more investors.

By: Wijayanto Samirin, co-founder and now director of Paramadina Public Policy Institute, and economic adviser to Indonesia’s Vice President Jusuf Kalla

This article is firstly published in the report of The Economist