Joint Declaration, 24 September 2022

We are an informal coalition of think tanks and civil society organisations that believes a robust global framework for the protection of intellectual property (IP) rights will play a key role in ensuring the world is prepared for future pandemics.

KEY POINTS

- IP rights are essential to develop and manufacture innovative pandemic vaccines and therapeutics.

- The best way to transfer technology and share manufacturing know-how is through voluntary cooperation.

- Relying on IP-free models of vaccine and therapeutic vaccine development is far too risky in a pandemic situation.

- In a pandemic, nimbleness and flexibility are key. UN organisations should not attempt to pick vaccine technology “winners” ahead of any pandemic.

- IP waivers are meaningless without robust public health and vaccine delivery systems.

This statement of principles outlines key innovation principles around IP learned from the Covid-19 pandemic, which we hope will inform formal negotiations for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response (PPR) Instrument shortly to begin at the World Health Organization (WHO).

In the Covid-19 pandemic, the IP system underpinned the development of multiple new safe and effective vaccines and therapeutics in record time and the manufacturing of billions of doses, saving hundreds of millions of lives. Voluntary manufacturing partnerships have been central to this success, with the IP system underpinning the safe and rapid transfer of the technical know-how necessary to manufacture these extremely complex innovative technologies.

As negotiators begin formal discussions on the Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response (PPR) Instrument at the World Health Organization (WHO) they should take note of the important role played by IP rights in the Covid-19 pandemic, and ensure that they maintain the solid legal protections provided by the TRIPS and other international agreements in the event of a new pandemic.

In particular, there should be no blanket IP waivers as has occurred recently in TRIPS, and the legal language of the instrument should ensure transfer of vaccine and therapeutic manufacturing technology takes place on a voluntary and cooperative basis. The inclusion of limitations on IP would leave the world exposed and reliant on unproven IP-free models of vaccine development in the event of a new pandemic.

And most essentially, focusing on improving public health infrastructure and vaccine delivery should be at the heart of any new PPR instrument. Indeed, the WHO has significant expertise in strengthening health systems, and should direct its time and resources towards areas where it has unique capabilities.

1. IP rights are essential to develop and manufacture innovative pandemic vaccines and therapeutics.

In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, a broad coalition of public health NGOs and public figures called for the suspension of IP rights, claiming that patents would hold up urgent research. As events demonstrated, these critics were wrong by a wide margin.

In January 2020 very little was known about Covid-19. By August 2022 there were ten Covid-19 vaccines authorised under emergency use listing by the WHO, and 778 unique active compounds in clinical development, including 234 vaccine candidates, 227 antivirals and 317 treatments.

Following the development of these innovative vaccines, opponents of IP rights called again for IP suspensions and waivers, this time claiming IP holds up manufacturing. In fact, the IP system presided over increases in global vaccine manufacturing on a scale never seen before. COVAX expects enough doses in 2022 to meet its commitments to participating countries. Globally there are now surplus Covid vaccines and therapeutics available, to the extent that certain vaccine manufacturers have had to issue costly write-downs for expired and surplus inventory.

The lesson from the Covid pandemic is that IP rights are fundamental to quickly developing and manufacturing at scale innovative vaccines and therapeutics. IP rights should therefore be protected and enshrined in any future pandemic treaty.

Research and development

IP rights were fundamental to the enormous success in Covid R&D seen over the last three years. IP has underpinned research partnerships and consortiums, allowing even commercial rivals to cooperate and share proprietary intellectual resources such as compound libraries. In the early stages of R&D, the public disclosure inherent to patent rights enables drug developers to identify partners with the right intellectual assets such as know-how, platforms, compounds and technical expertise. Without patents most of this valuable proprietary knowledge would be kept hidden as trade secrets, making it impossible for researchers to know what is out there.

Additionally, the existence of laws protecting intellectual property helps rights-holders make the decision to collaborate in the first place. By allaying concerns about confidentiality, IP rights enable companies to open their compound libraries, and to share platform technology and know-how without worrying they are going to sacrifice their wider business objectives or lose control of their valuable assets.

Manufacturing

IP rights have also been the bedrock of rapid mass manufacturing scale-up, either via out licensing to manufacturers in other countries, like Astra Zeneca, or subcontracting discrete parts of the manufacturing value chain as in the case of Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna.

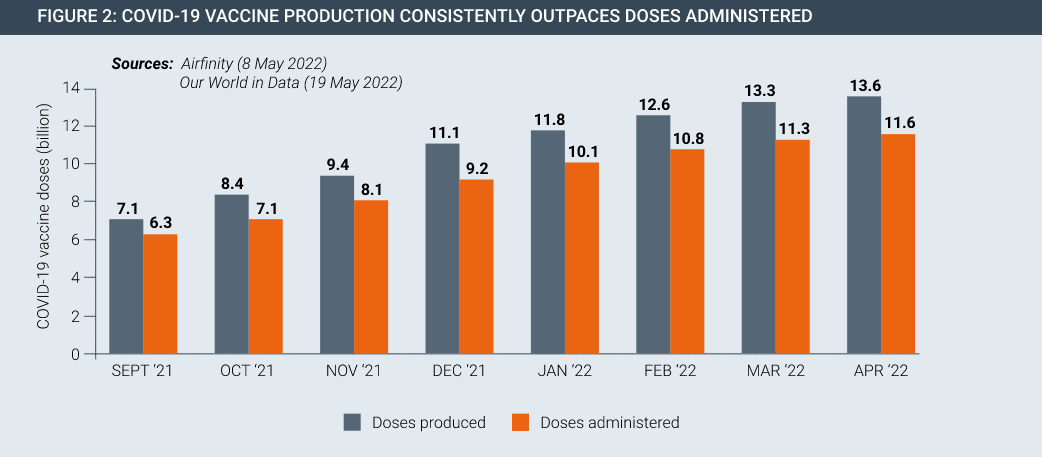

From a standing start in 2020, the scale-up of COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing has been remarkable. Currently, vaccine supply far exceeds the global capacity to administer safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines in an equitable manner, yet a range of non-IP challenges relating to public health infrastructure, vaccine hesitancy and other problems mean that vaccine roll-outs have been slow.

IP rights have been fundamental to this massive, rapid scale-up of vaccine manufacturing by allowing innovator companies to enter into manufacturing partnerships all over the world. They establish the trust necessary for the safe transfer of valuable manufacturing know-how without fear of it being misused for commercial gain.

In the case of voluntary licensing which underpins manufacturing of the Oxford / AstraZeneca vaccine, IP rights enabled the selection of reliable and high-quality partners in multiple countries. Similarly, Pfizer and BioNTech built a network of partners for manufacturing their vaccine, which included some of Pfizer’s largest competitors.Such voluntary relationshipsshow that IP rights provide a framework for robust and rapid technology transfer free from the reluctance, legal resistance, and natural cautions that would inevitably arise if a pandemic treaty were to weaken IP rights.

2. The best way to transfer technology and share manufacturing know-how is through voluntary cooperation.

Early official discussions around the PPR instrument stress the importance of “mechanisms that promote and provide relevant technology transfer and know how.” These mechanisms should be voluntary and based on partnership and collaboration.

Manufacturing partnerships were at the heart of the huge scale up in Covid-19 vaccine production. Importantly, this happened on a voluntary basis without the need for coercive measures by government. Innovators shared complex manufacturing know-how and recipes with partners all over the world, with these partnerships underpinned by the protection of intellectual property rights.

Some argue that innovators should be forced to transfer manufacturing know-how in the PPR instrument. This should be avoided at all costs.

For small molecule drugs, it is easy for a generic manufacturer to reverse engineer and manufacture a patent protected medicine. Modern vaccines and many therapeutics are far more complex. Most vaccine and biologic medicine production technology is not embodied by patents, but rather in technical know-how which is not easily transferred. Such information is often known by few people within the innovator organisation. Most vaccine manufacturers in developing countries lack this knowledge and without it they cannot simply or quickly repurpose their factories.

Transferring this technical knowledge is not a simple matter of reviewing patents and other public sources. Rather, it must be taught.

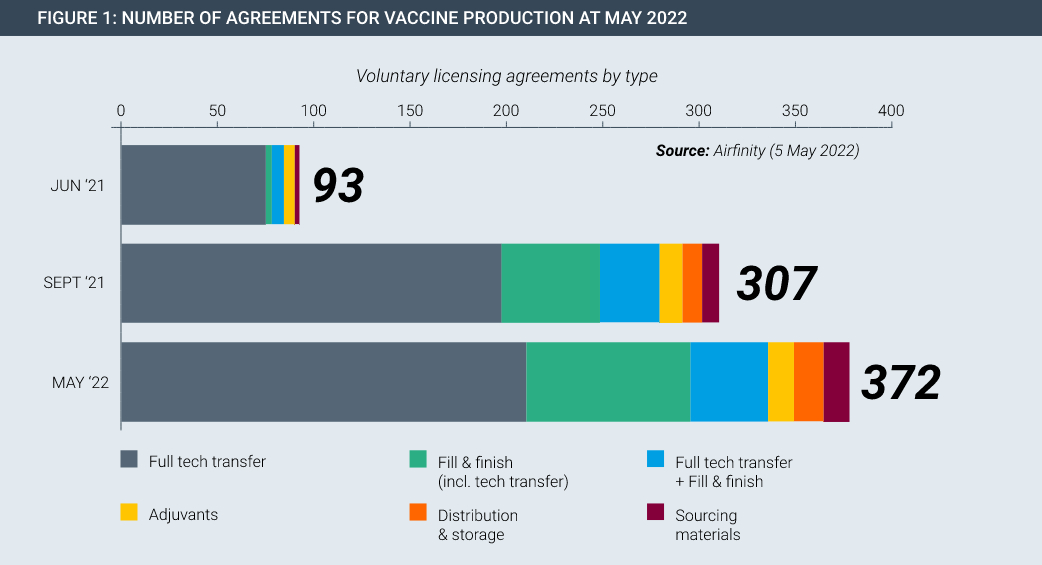

In the Covid pandemic, technology transfer happened on a large scale on a voluntary basis. For example, Pfizer/BioNtech and Johnson & Johnson each partnered with Merck to increase production of their cutting-edge vaccines. In fact, partnerships span the entire manufacturing value chain, existing in every continent and have been rapidly rising in number (Figure 1). Each of these partnerships involved huge transfers of data and know-how, with dozens of specialist staff from the innovator spending time with the partner to teach and oversee the safe and accurate transfer of manufacturing knowledge.

In each case, however, trade secrets and other proprietary information are protected with both trade secrecy agreements and the existence of laws protecting IPRs. Compulsory technology transfer in a pandemic preparedness treaty would require innovators to reveal their know-how under threat of legal force, with very different consequences than voluntary cooperation.

First, forced transfers would likely be contested both in law and fact, as innovators would hardly be keen to divert their most knowledgeable and busy employees during a global crisis. Transferring this know-how could take many months, followed by further delays while regulators scrutinise any new manufacturing facilities and their products for quality standards. Pandemic-related travel restrictions would make this process even more difficult.

Moreover, forcing the disclosure of a trade secret destroys it, as it is no longer secret. Secrecy is the fundamental legal and practical requirement for the existence of a trade secret. When a patent owner is compelled to license a patent, it still owns the patent and can receive a reasonable royalty. By contrast, forced disclosure destroys a trade secret and its value.

If governments were to force technology transfer it would therefore represent a fundamental assault on private property rights and contract law which would have disastrous economic implications beyond the pandemic. At the very least it would destroy the value of that many small biopharmaceutical companies whose main assets are the IPRs they hold around small numbers of technologies.

Voluntary technology transfer based on cooperation, appropriate training and resource sharing is therefore key to establishing additional capacity in the event of a future pandemic.

3. Relying on IP-free models of vaccine and therapeutic vaccine development is far too risky in a pandemic situation.

The R&D and manufacturing model which delivered for Covid was based on secure IP rights. Yet some governments and public health activists argue that a new pandemic treaty should waive IP rights at the outset of a new pandemic in order to promote access. If a new treaty were to take IP rights off the table at the commencement of any new pandemic, the world would be forced to rely on experimental, non-IP models of vaccine and therapeutic development and manufacture. This would leave the world at grave risk in the event of a future pandemic.

Although some non-IP based Covid vaccine development projects were attempted during the Covid-19 pandemic, their outcomes were underwhelming:

- V The University of Helsinki vaccine has been unable to secure the necessary funding for clinical trials for its IP-free vaccine, and there are currently no details about the preclinical studies available publicly.

- V Corbevax, a patent-free vaccine developed by a consortium including the Texas Children’s Hospital has been authorised for use in India, although details from its clinical trials were not made public until mid-2022: well after the 2021/2 omicron wave had peaked.

The slow progress of these projects relative to their IP-based rivals is largely due to their difficulties in attracting the huge amounts of capital necessary to advance rapidly through clinical trials and establish large levels of manufacturing capacity. The ability to secure large amounts of investment for risky research endeavours that are likely to fail is a significant feature and benefit of IP rights.

IP-free models of vaccine development are therefore unreliable in a pandemic situation, where speed is crucial. By contrast, vaccines that have leveraged IP rights have moved quickly through clinical development, regulatory authorization, and into mass manufacture and distribution.

4. In a pandemic, nimbleness and flexibility are key. UN organisations should not attempt to pick vaccine technology “winners” ahead of any pandemic.

The Covid pandemic has seen a renewed intergovernmental emphasis on South-South collaboration, in particular an ambition for less developed countries in Africa and elsewhere to become self-sufficient in vaccine manufacturing. One outcome of this is the WHO mRNA vaccine hub, in which a central “hub” offers training and technology transfer advice to “spoke” manufacturers in other countries. Financial support is offered by the IMF, GAVI and others.

While the goal of increasing global manufacturing capacity is laudable, the approach in which a central governmental agency such as WHO decides in advance which vaccine platform technology (in this case mRNA) should be the centre of global efforts is fundamentally flawed:

- mRNA based technology has not been approved by a stringent regulatory authority for any indication other than Covid-19. While the technology shows promise for other diseases and indications, no products other than for Covid-19 are currently available. Should the technology not live up to its hype, countries that have invested significant sums in mRNA manufacturing plants will be left with costly white elephants.

- Similarly, the next pandemic may not be addressable by mRNA-based vaccines. Putting all the eggs in one basket through significant public investment in developing country mRNA plants at this stage could leave the world wrong-footed in the next pandemic.

- With Covid gradually receding as a public health threat, it is not clear from where ongoing demand will come from for the vaccines produced by these plants. mRNA vaccine manufacturing is complex and plants cannot just be switched on and off. Significant ongoing public investment will be required.

- Focusing scarce resources on these new vaccine technologies could cause existing manufacturing plants to shift activities away from producing vaccines for which there is clear and ongoing demand. This would have serious public health ramifications.

There are parallels with today’s attempts to build vaccine manufacturing capacity in less developed countries with efforts by multilateral and overseas development agencies to establish anti-retroviral (ARV) manufacturing capacity in Africa in the 2000s. Like today, the aim was also to secure sustainable access to medicines and increase technical and industrial capacity of countries.

In 2005 a World Bank summary of the evidence surrounding local production of pharmaceuticals, concluded that producing medicines domestically in many parts of the world makes little economic sense: “If many countries begin local production, the result may be less access to medicines, since economies of scale may be lost if there are production facilities in many countries,” the authors concluded.

The evidence since gathered bears this out. Researchers have been able to find little evidence that local production strategies facilitate access to medicines, nor that it achieves the other benefits claimed by its proponents, such as foreign import savings, enhanced human capital and greater local innovative capacity.

Other researchers looking at specific case studies have found some initial successes in establishing facilities in Africa, but little answer to the question of how they will be sustainable in the absence of substantial ongoing foreign financial assistance.

A major challenge faced by African ARV manufacturers was how to become competitive against rivals from India and elsewhere. In many cases this never happened. One major review of ARVs locally manufactured under compulsory license in Africa were found to

be substantially more expensive than those procured on global markets through the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, UNICEF and other international channels.

In the cases of Zimbabwe, Zambia and Mozambique, local manufacturers working under compulsory license found themselves eventually displaced by Indian generic manufacturers, who were able to produce ARVs more cheaply. The cost of imported APIs

was a major competitive constraint. For mRNA vaccines, which rely on hundreds of imported subcomponents and manufacturing parts and supplies, these costs could be even more significant.

For ARVs, supporters of local manufacturing could at least point to sustainable and ongoing demand for the products. There is no such certainty for mRNA vaccines. Demand for Covid mRNA vaccines is already declining significantly and is likely to decline still further as Covid recedes as a public health threat. This has already led to inventory write-offs in 2022 of USD800m for Moderna alone.

There is no guarantee that the next pandemic will be addressable by mRNA-based vaccines. government investment in such facilities in Africa and other less developed regions to tackle future pandemics is highly speculative and likely to result in significant wastage of public funds. These funds could be directed to more effective public health measures, such as building vaccine delivery capacity.

5. IP waivers are meaningless without robust public health and vaccine delivery systems

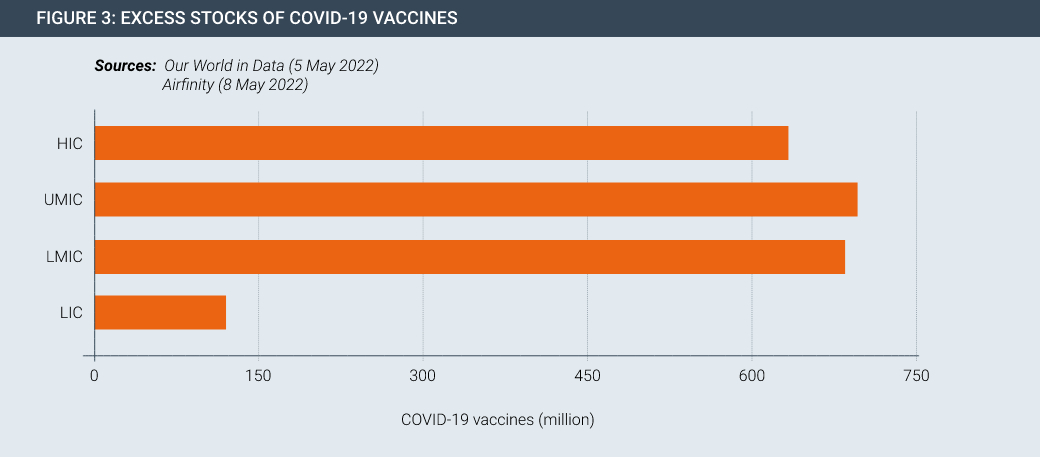

Vaccine and therapeutic innovation is meaningless without delivery. Despite the progress made in developing and manufacturing new products, they are not necessarily getting to people in developing countries in sufficient quantities. This seen by the fact that there is currently surplus stock of Covid-19 vaccines both at a global level and for countries at all levels of development (Figures 2 and 3).

About 40% of vaccines that have arrived so far on the African continent have not been used, according to data from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, a policy think-tank. Meanwhile, the first Covid vaccine manufacturing facility on the African continent, managed by Aspen in South Africa, may soon pivot to other products due to lack of demand.

At the root of the problems in administering vaccine are weaknesses in local health systems and vaccine delivery. There are multiple barriers to vaccine delivery that must be addressed to prepare for future pandemics. None of them have anything to do with intellectual property rights:

- WHO estimates a projected shortfall of 18 million health workers by 2030, mostly in low- and lower-middle income countries.

- Weaknesses in the cold supply chain such as too few fridges, inadequate ice packs and vaccine carriers, unreliable power supply, and a shortage of biomedical engineers to maintain fridges and cold vans.

- A predicted shortfall of up to 2.2 billion auto-disable syringes, designed to prevent syringe re-use and crucial to low and middle-income countries.

- Widely documented vaccine hesitancy

- Difficulties accessing vaccination sites due to public transport costs and shortcomings, and potential lost earnings. The need to get double doses and boosters can further dissuade people.

These very real issues are key to the rapid and effective delivery of vaccines and therapeutics in the event of a pandemic. Their mitigation should therefore be at the heart of the new treaty on pandemic preparedness.

This declaration is supported by:

- Adam Smith Centre, Singapore

- Alternate Solutions Institute, Pakistan

- Austrian Economic Centre

- Centre for Development Policy and Practice, India

- Competere – Policies for Sustainable Development, Italy

- Centre for Indonesian Policy Studies

- Consumer Choice Centre, Brussels

- Fundación Eleutera, Honduras

- Fundación IDEA, Mexico

- Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy, Malaysia

- Geneva Network, United Kingdom

- Hayek Institute, Austria

- I-Com, Institute for Competitiveness, Italy

- Imani Centre for Policy and Education, Ghana

- Instituto de Libre Empresa, Peru

- Instituto de Ciencia Politica, Colombia

- Istituto Bruno Leoni, Italy

- Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, United States

- Laboratory of Industrial and Energy Economics,

- National Technical University of Athens, Greece

- Libertad y Desarrollo, Chile

- Libertad y Progreso, Argentina

- Macdonald Laurier Institute, Canada

- Paramadina Public Policy Institute, Indonesia

- Property Rights Alliance, United States