Ika Karlina Idris and Nuurrianti Jalli

28 April 2020

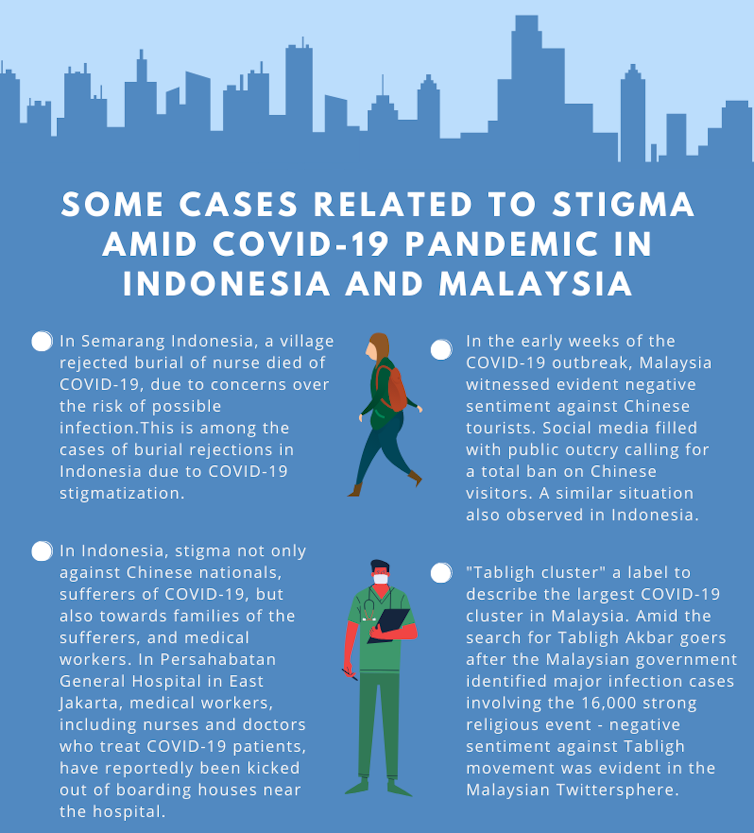

As COVID-19 continues to ravage Southeast Asian countries, the public in both Indonesia and Malaysia shares the trait of blaming others for the pandemic.

In Indonesia, people believe the virus came to Indonesia due to the government’s weak policy on Chinese workers and tourists. As of April 28, Indonesia has recorded 9,096 positive cases and the highest fatality rate in the region.

Malaysian people blame a group of Muslim pilgrims to a big religious gathering with more than 16,000 participants. The event led to a sudden spike of COVID-19 cases in Malaysia. Malaysia has confirmed almost 6,000 positive cases as of April 28.

We found this similar pattern between the two countries after investigating conversations in Indonesia and Malaysia’s twitterspheres in March 2020.

Since the first case in January, conversations on COVID-19 have flooded social media, including Indonesian and Malaysian internet spheres.

With active social media users in both countries, analysing these conversations could help us understand public opinion on COVID-19.

In our newly concluded yet unpublished research, we found these “blaming others” attitudes related to stigmas surrounding COVID-19 in both countries.

From stigma to blaming others

Since COVID-19 was first reported in China, increased cases of stigmatisation and prejudice have been recorded across the world.

This includes stigma against Asian people, COVID-19 patients and even medical workers.

Our research collected 450,000 Twitter conversations posted in March 2020 to check how COVID-19-related stigma existed in Indonesia and Malaysia’s public sphere.

Due to the huge number of shared messages in Twitter, we cleaned the data by deleting all retweets and ended up having 23,527 original tweets.

Through a simple random sampling method, we selected 6,932 tweets — 5,983 tweets from Indonesia and 949 from Malaysia. We then analysed these using quantitative content analysis. Two human coders who understand both Bahasa Indonesia and Malay were involved in analysing the data.

In Indonesia, we found the majority of stigma was related to prejudices against Chinese people. The sentiment went further with the public blaming the government for still allowing tourists and workers from China to come into the country even after the pandemic had started in some countries.

There was also a strong sentiment that the Chinese deserved the virus because of their repression of Muslims in Ughur.

In Malaysia, most of the tweets blamed other Malaysians, especially a group of Muslim pilgrims who organised a big religious gathering in Sri Petaling, Malaysia, where many participants were infected.

The organisers were stigmatised due to their recklessness in risking many people being infected at their event despite warnings from authorities.

Theories on stigma

American sociologist Erving Goffman defines stigma as “a discrediting attribute resulting from social construction”. Stigmas can be based on one’s physical condition, negative characteristics, or backgrounds such as race, gender or ethnicity.

In our research, we discovered that tweets from both countries showed one’s background came out as the main object.

In Malaysia, one’s background accounted for 95.8% of stigma in tweets, followed by characteristics (4.2%). In Indonesia, we found 69.3% of stigma related to one’s background, followed by characteristics (28.1%) and physical conditions (2.6%).

Stigma has at least five factors: labelling, negative attribution, separation, status loss, and controllability.

The dimension of labelling is related to “the act of assigning an unfavourable descriptor to a problematic condition”.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia and Malaysia, this kind of stigma includes using the words “China” or “Chinese” to describe the disease.

The dimension of negative attribution incorporates negative terms to describe the person who has the disease or even the family members of confirmed cases.

The third dimension of separation can be understood from the view that the person with an unfavourable condition cannot have contact with other people.

The dimension of status loss reflects situations where a patient or their family loses their privilege or social recognition, including housing, education, employment and health care.

The last dimension, controllability, is related to one’s capacity to control the situation to avoid unfavourable conditions, including the responsibility for preventing such situations. If this person fails to do that then he or she will be stigmatised.

In Malaysia, it was the failure of the religious group to act on their responsibility to prevent the event from taking place amid the pandemic that came out as the main stigma, followed by “labelling” (14.6%) and “separation” (2.1%).

In Indonesia, we found the main stigma was related to “labelling” (86.1%), followed by “controllability/responsibility” (7.9%), “negative attribution” (3%), “separation” (2%) and “status loss” (1%).

Beyond stigma

While we aimed to look for stigma related to COVID-19, we found the tweets containing elements of stigmatisation were not as dominant as the evaluation of governments’ responses.

In Indonesia, most of the tweets contained criticism and negative sentiment towards the Indonesian government and its policies in handling the COVID-19 pandemic. In Malaysia, most tweets were related to the government’s appeal to stay home.

Specifically in Indonesia, we found conversations related to stigmas accounted for less than 6% (310 tweets) compared to criticisms of the government’s bad performance in handling the pandemic at 84.6% (4,987 tweets). (*)

This article first appeared on The Conversation